Rosemary’s Remembrances: When Elvis Came to Lexington

February 6, 2024

Barbara Allen

February 14, 2024Brown Mountain Lights

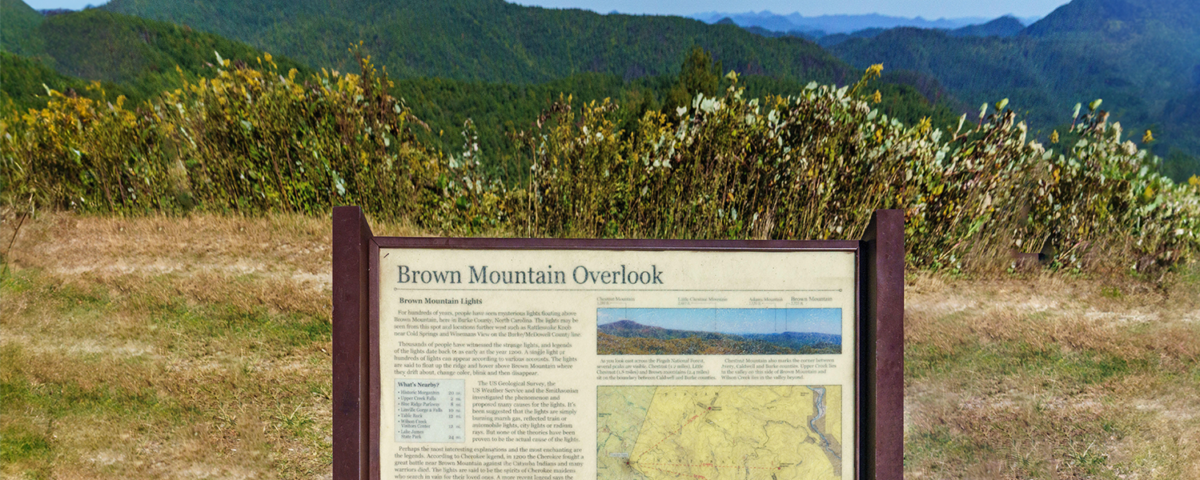

The Appalachian range, known for its lush greenery and striking peaks, also hosts one of the most intriguing and enduring mysteries of North Carolina—the Brown Mountain Lights. These peculiar illuminations, appearing regularly over the Brown Mountain in the Linville Gorge area, have fascinated observers for centuries, inspiring a myriad of theories and extensive research.

The inexplicable light show ranges from red to blue to white glows, sometimes remaining stationary, sometimes darting around the night sky. Native American lore attributes these lights to ghostly spirits, while some folklore suggests they are the spectral lanterns of grieving widows searching for their fallen husbands.

In the age of advanced scientific analysis, other explanations have been postulated, going beyond the realm of geologic or atmospheric causes. Some researchers have considered the possibility of piezoelectric effects, wherein the Earth's crust produces lights when under stress. This could be caused by the underlying tectonic activity, creating electrical discharges visible on the mountain's surface. Additionally, there have been discussions around atmospheric reflections, where light from other natural sources is bent and reflected due to unique atmospheric conditions over Brown Mountain.

Another captivating theory stems from biology. Certain fungi and microbes, known to emit a soft glow, might be responsible. While bioluminescence is common in marine environments, terrestrial bioluminescence is rarer but not unheard of. The presence of such organisms, in high enough concentrations, could explain the mysterious lights.

As each theory emerged, so did the efforts to validate or refute them. Scientists have pointed to refracted light from locomotives, cars, and local settlements. However, this explanation fails to account for sightings recorded prior to the invention of these artificial light sources.

As public curiosity grew, the mystery caught the attention of the U.S. Geological Survey. In 1922, geologist George R. Mansfield was dispatched to Brown Mountain to study this phenomenon. Through a careful and systematic approach, Mansfield spent considerable time observing, documenting, and analyzing the lights. His investigation, encompassing meticulous observation and logical reasoning, led to a series of conclusions which were subsequently released to the press.

The intrigue surrounding the Brown Mountain Lights endures, with Mansfield's study providing only one among many possible explanations. What is certain is that these lights continue to captivate and inspire both the scientific community and the public alike, remaining one of nature's most enigmatic spectacles. As for Mansfield's conclusions? We leave it to his own words in the abridged version of his report to reveal his findings. Download the full version here.

Origin of the Brown Mountain light in North Carolina

By George Rogers Mansfield

GOVERNMENT INVESTIGATIONS MADE For many years "mysterious lights" have been seen near Brown Mountain, in the northern part of Burke County, N.C., about 12 miles northwest of Morganton. Some have thought that these lights were of supernatural origin; others have dreamed that they might indicate enormous mineral deposits; and many who have not had such visions have looked upon them as a natural wonder that lent interest to all vacation trips to the region. In October 1913 at the urgent request of Representative E. Y. Webb, of North Carolina, a member of the U.S. Geological Survey, D. B. Sterrett, was sent to Brown Mountain to observe these lights and to determine their origin. After a few days investigation Mr. Sterrett declared that the lights were nothing but locomotive headlights seen over the mountain from the neighboring heights. This explanation was too simple and prosaic to please anyone who was looking for some supernatural or unusual cause of the lights, and when they were seen after the great flood of 1916, while no trains were running in the vicinity, even some of those who had accepted Mr. Sterrett's explanation felt compelled to abandon it. As time went on, the interest in the lights became more general, and as one after another local investigator failed to discover their origin, the mystery seemed to grow deeper. Finally Senators Simmons and Overman prevailed upon the Geological Survey to make a second and more thorough investigation of these puzzling lights. The present writer, to whom the task of making this investigation was assigned, spent 2 weeks near Brown Mountain in March and April 1922 and took observations on seven evenings, on four of them until after midnight, from hillsides that afforded favorable views of the lights. The results of the work are reported here.

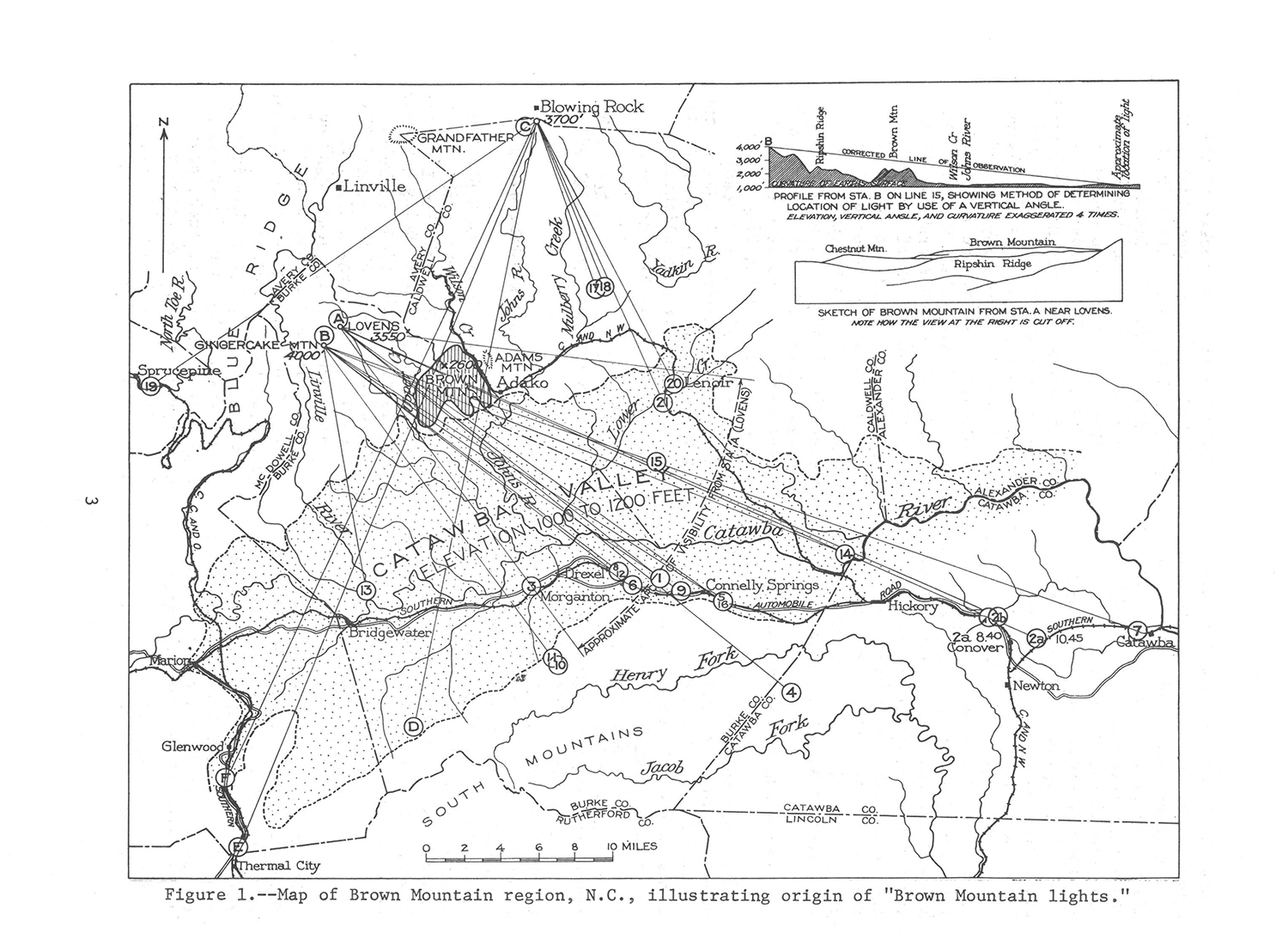

TOPOGRAPHY OF BROWN MOUNTAIN

The shape and general elevation of Brown Mountain are shown on the accompanying map. Its eastern ridge forms part of the boundary between Burke and Caldwell Counties. Its top is plateau-like and reaches a maximum elevation of about 2,600 feet. It is partly cut away by southward-flowing branches of Johns River and is separated from more intricately carved uplands on the northwest, north, and northeast by Upper and Wilson Creeks and their tributaries. Seen from a distance from almost any direction, Brown Mountain appears as a ridge having a nearly even skyline. (See map , fig • 1. ) GEOLOGIC FEATURES The geologic features of the Brown Mountain region are the southward extension of the features seen farther north, which are described and mapped in the Cranberry-folio, No. 90 of the series of folios of the Geologic Atlas of the United States. There is nothing unique or unusual in t~e geology of Brown Mountain. Most of the mountain is composed of the Cranberry Granite, a rock which also underlies many square miles on the north side of the Blue Ridge. The Caldwell Power Co. has drilled a series of holes, 50 to nearly 100 feet deep, along the lower part of the east slope of Brown Mountain preliminary to the location of a tunnel. Through the kindness of H. L. Millne~ an officer of the company; the writer was permitted to examine the cores taken from these holes. Most of them consisted of ordinary granite,· though a few included masses of rock of other kinds. The men who surveyed the line for the tunnel reported local magnetic attraction amounting to a deflection of about 6°, but though representative pieces of all the different kinds of cores were presented to the compass needle, they produced no noticeable effect. Dip-needle tests made to determine magnetic conditions at Brown Mountain gave readings of 41~0 , which is slightly greater than those made at Loven's or at Gingercake Mountain (40°) but less than those made at Blowing Rock (43°) and at the Perkins place, near Adako (45°).

RECORDS OF EARLIER OBSERVATIONS

So far as the writer is aware the first published account of the light was given in a dispatch from Linville Falls to the Charlotte Daily Observer, dated September 23, 1913, in which its discovery is credited to members of the Morganton Fishing Club, who saw it "more than two years ago" but who were "laughed at and accused of seeing things at night." This account is quoted in part below: · .. The mysterious light that is seen just above the horizon almost every night from Rattlesnake Knob, near Cold Spring, on the Morganton road is still baffling all investigators. With punctual regularity the light rises in a southeasterly direction from the point of observation just over the lower slope of Brown Mountain, first about 7:30 p.m. and again at 10 o'clock. It looks much like a toy fire balloon, a distinct ball, with no atmosphere about it. It is much smaller than the full moon, much larger than any star and very red. It rises in the far distance from beyond Brown Mountain, which is about 6 miles from Rattlesnake Knob, and after going up a short distance, wavers and goes out in less than 1 minute. It does not always appear in exactly the same place, but varies what must amount in the distance to several miles. The light is visible at all seasons, so Mr. Anderson Loven, an old and reliable resident testifies.

There seems to be no doubt that the light rises from some point in the wide, level country between Brown Mountain and the South Mountains, a distance of about 12 miles, though it is possible that it rises at a still greater distance. In this article in the Charlotte Daily Observer, the discovery of the lights is assigned to a date "more than 2 years ago," but conversation with B. S. Gaither, of Morganton, who participated in the fishing party mentioned, and who was the one who first saw the lights, elicited the fact that they were observed in 1908 or 1909. Rev. C. E. Gregory, who in 1910 built a cottage on the little knoll near Loven's Hotel at Cold Spring, presumably the Rattlesnake Knob referred to, was, according to local oral accounts, the first to give much attention to the lights and to bring them to public notice. Col. Wade H. Harris, editor of the Charlotte Daily Observer, from which the first description of the light, quoted above, was taken, states in a letter dated October 2, 1921, addressed to Senator Simmons~ that "there is a record that it (the light) has puzzled the people since and before the days of the Civil War." R. T. Claywell, of Morganton, says that people used to come to Burke County 60 years ago to see the lights. Joseph Loven, of Cold Spring, says that he noticed the lights as early as 1897, when he moved to his present home by Loven's Hotel, but that he had heard nothing about them and paid no attention to them until Mr. Gregory came, in 1910. In October 1913, Mr. Sterrett of the U.S. Geological Survey made his investigation, as a result of which he decided that the lights were locomotive headlights. He did not visit Rattlesnake Knob but went unaccompanied to the Brown Mountain region, where he made his observations.

NATURE AND APPEARANCE OF THE LIGHT

In his letter to Senator Simmons already cited, Colonel Harris writes as follows concerning the light: "It is a pale white light, as one seen through a ground glass globe, and there is a faint, irregularly shaped halo around it. It is confined to a prescribed circle, appearing three or four times in quick succession, then disappearing for 20 minutes or half an hour, when it repeats within the same circle." Prof. W. G. Perry, of the Georgia School of Technology, in a letter dated December 15, 1919, addressed to Dr. C. G. Abbot, of the Smithsonian Institution, describes the light as seen from the Cold Spring locality as follows: "We occupied a position on a high ridge. Across several intervening ridges rose Brown Mountain, some 8 miles away. After sunset we began to watch the Brown Mountain direction. Suddenly there blazed in the sky, apparently above the mountain, near one end of it, a steadily glowing ball of light. It appeared to be about 10° above the upper line of the mountain, blazed with a slightly yellow light, lasted about half a minute, and then abruptly disappeared. It was not unlike the "star" from a bursting sky rocket or Roman candle, though brighter.

We were impressed with the following facts: The region about Brown Mountain and between our location and the mountain is a wild, practically uninhabited mountain region--a confusion of mountain peaks, ridges, and valleys. Viewing the lights from a fixed position our estimate of their location was most inexact; the varying color (almost a white, yellowish, reddish) may have been due to mist in the atmosphere; the view of the lights was a direct one and not a reflection; there seemed to be no regularity in their time of appearance; they came suddenly into being, blazed steadily, and as suddenly disappeared; they appeared against the sky and not against the side of the mountain.

THE INVESTIGATION IN 1922: METHODS EMPLOYED

The writer set out to take observations at the place near Loven's Hotel and at other places from which, according to reports, the lights could be seen, Brown Mountain itself being one of the places. The instruments used consisted of a 15-inch planetable (a square board mounted on three legs), a telescopic alidade, pocket and dip-needle compasses, a barometer for measuring elevations, a fieldglass, a flashlight, and a camera, besides topographic maps of the region. In making the observations a topographic map was fastened flat on the board, which was leveled and the map turned to a position in which the directions north, south, east, and west on the map correspond with the same directions on the ground. Sights were then taken to known landmarks with the alidade, which is essentially a ruler fitted with a sighting telescope, and corresponding lines were drawn along the ruler on the map. The meeting point of the lines thus drawn marked the location of the observer's instrument on the map. From this location sights were taken at night with the alidade on the map. The telescope of the alidade swings in a vertical as well as in a horizontal plane and can therefore be used for measuring vertical angles along the lines of sight. The dipneedle compass is so arranged that the needle swings in a vertical instead of in a horizontal plane. It is used to detect differences in magnetic attraction. Three stations were occupied--one on the knoll by the cottage formerly occupied by Rev. C. E. Gregory, near Loven's Hotel; one in a field on the east slope of Gingercake Mountain; and one on the terrace in front of the summer residence of Miss Cannon, at Blowing Rock. These stations are marked on the map (fig. 1) by the letters A, B, and C, respectively. Two nights were spent on Brown Mountain, but the conditions were so unfavorable that no station was occupied there. At each station at which observations were made, vertical angles to parts of Brown Mountain were noted, dip-needle readings were made, and photographs were taken. Vertical angles were also measured when practicable from each station to each light seen. The procedure adopted was first to get a line of sight to the light and then to note its time of appearance and measure its vertical angle, but occasionally a light remained visible for so short a time that it had disappeared before 1 the telescope could be trained upon it and a line drawn to fix its direction. Few records were kept of lights for which lines of directions were not drawn, but the total number may have been nearly twice the number recorded. The atmosphere proved too hazy for satisfactory photographs. The train registers at Connelly Springs and at Hickory were examined, and subsequently train schedules for the evenings of observation were obtained from many station agents throughout the region. The observations obtained in the field were afterward adjusted on the map. Many profiles along lines of sight were constructed, the vertical angles were plotted, and corrections for the curvature of the earth's surface and for refraction were made. In this way the sources of some of the lights were approximately determined.

Figure 1 illustrates the method of locating a source of light by means of a profile and vertical angle drawn from station B along line 15. Space does not permit a detailed statement of the individual observations made and of the inference drawn from them. The geographic positions of the sources of light as determined by instrumental observations are only approximate because of the difficulties attending the use of the instruments in darkness. The stations were from 1,000 to 1,500 feet higher than the summit of Brown Mountain, so that the lines of sight to the lights seen all passed several hundred feet above the top of the mountain as shown in inset profile (fig. 1). This fact caused the lights to appear over the mountain rather than on or below its crest, a feature noted both in the first published description of the lights, in the Charlotte Observer, and in Professor Perry's description, ·already quoted. The appearance of the lights as described in these two accounts, especially in that given by Professor Perry, agrees so closely with their appearance as observed by the writer that no additional description of them need be given here.

OBSERVATIONS AT LOVEN'S

At station A near Loven's Hotel, various lights were observed and studied. The lights were seen in an arc between Lenoir and line 3 over Brown Mountain, associated with the name "Brown Mountain light." Observations included lights from trains, automobiles, and an unexplained light, possibly the Brown Mountain light, viewed at different times and positions.

OBSERVATIONS AT GINGERCAKE MOUNTAIN

At station B on Gingercake Mountain, the lights were seen over a larger arc with Brown Mountain covering half of it. Observations included lights from locomotives, automobiles, and possibly brush fires. There was a notable observation of a light near the dam on Linville River. Various lights seemed similar, and unfavorable conditions led to limited observations on certain nights.

OBSERVATIONS AT BROWN MOUNTAIN

An expedition to Brown Mountain was hindered by rain and fog. While no lights were seen, the conditions and the circuit made around the mountain made it likely that any lights arising over the mountain would have been noticed, but none were observed.

CONCLUSIONS

The writer feels confident that the lights he saw were actually a fair average display of the so-called Brown Mountain light. The lights observed have nothing in common with the Andes light or with St. Elmo's fire. There is no geologic basis for the idea that the lights seen are natural wonders of any sort, but there are certain interesting surface features and atmospheric conditions that are effective in producing some of the appearances of the light.

By reference to the map it will be noted that the Catawba Valley east of Marion is a basinlike area--an area nearly surrounded by mountains, of which the Blue Ridge on the north, with its fringe of southward-projecting spurs, is the highest and most rugged part. After sunset cool air begins to creep down the tributary valleys into the basin, but the air currents come from different sources and are of different temperature and density. The atmospheric conditions in the basin are therefore very unstable, especially in the earlier part of the evening, before any well defined circulatory system becomes established. At any given place in the basin the air varies in density 15 degrees during the evening and hence in refractiveness. The denser the air, the more it refracts light or bends waves of light emanating from any source. The humidity of the air affects its density and hence its refractive power. Mist, dust, and other fine particles tend to obscure and scatter the light refracted and to impart to it the reddish or yellowish tints so frequently observed. Thus it is that the light is most active in a clearing spell after a rain, as noted by many observers. When the mist is very dense, the light is completely obscured. Lights that arise from any source in the basin are viewed at low angles.

Probably few if any basins on the Blue Ridge front are so favorably located as to show as well as this one the atmospheric phenomena described, and the opportunities here for the observation of such phenomena are perhaps no less exceptional. Loven's Hotel and Blowing Rock, which are resorts that attract fishermen or tourists, are among the most favorable places of observation. The valley is fairly well settled and has a network of roads, three railroads, and several large towns, so that the possible sources of light are very numerous. As the basin and its atmospheric conditions antedate the earliest settlement of the region, it is possible that even among the first settlers some favorably situated light may have attracted attention by seeming to flare and then diminish or go out. As the country became more thickly settled the number of chances for such observations would increase. Before the advent of electric lights, however, it is doubtful whether such observations could have been sufficiently numerous to cause much comment, though some persons may have noted and remarked upon them.

According to local estimates electric lights have been in use in the larger towns of the region for about 30 years. The use of powerful electric headlights on railway locomotives, which began about 1909, furnished new sources of strong lights in the valley and introduced an element of regularity in their appearance. In 1910, the Brown Mountain light began to acquire notoriety. Meanwhile, automobiles were coming into use throughout the country, and many of them were equipped with powerful headlights. Within the last few years their number has been greatly increased, and this fact is in keeping with the general deduction already made--that on a favorable evening the lights are seen more frequently now than formerly. During the flood of 1916, when train service was temporarily discontinued, the basin east of Marion, where the atmospheric conditions are disturbed, was still the scene of the intermittent flare of favorably situated lights. Automobiles were then in use in the larger towns and on some of the intervening roads, and their headlights were doubtless visible from Loven's over Brown Mountain. One need only remember the network of roads in the valley region (see topographic maps of the Morganton and Hickory quadrangles) to realize the almost infinite number of possibilities for automobile headlights to be pointed toward Brown Mountain and stations of observation beyond. It should be emphasized, too, that automobile headlights and locomotive headlights, when seen at distances and under atmospheric conditions such as those which prevail in this region, possess no characteristic that clearly distinguishes them from other lights. On the contrary, as stated by the lady at Blowing Rock, they look "as much alike as so many peas in a pod," though this statement should not be understood to mean that some may not be brighter than others.

The behavior of headlights in the Brown Mountain region in this respect is comparable to that of the lights in the lighthouses on the Atlantic Coast. From the seawall at Gloucester, Mass., the writer has repeatedly seen the light at Minots Ledge, southeast 17 of Boston, nearly 25 miles away in a direct line. This light is identified by a series of flashes that may be represented by the numerals 1-4-3. There is no beam and there are no rays. The light cannot be seen unless the air is fairly clear. Then it simply flashes once, four times, three times, and it has much the same appearance as the Brown Mountain light. The supposed motion of the light at times may be due to errors of observation.

Some years ago McNeilly Du Bose, an engineer then employed near Morganton, tested observations made by himself and others by tying a cord across the fork of a tree in a place where he could see the light across the cord and was surprised to find that the light was stationary with respect to the cord. Professor Perry, whose letter has been quoted, notes that the light was uniformly stationary when he saw it. The eye is easily deceived at night as to the stability or motion of an object, and an observer's impressions are to a considerable extent affected by his mental and physical condition at the time of observation. It is not surprising that under the circumstances different eyewitnesses give quite different accounts of the light, especially as the light may appear suddenly against a dark background with nothing nearby that can be used as a scale to determine its size or its possible motion.

In summary it may be said that the Brown Mountain lights are clearly not of unusual nature or origin. About 47 percent of the lights that the writer was able to study instrumentally were due to automobile headlights, 33 percent to locomotive headlights, 10 percent to stationary lights, and 10 percent to brush fires.

-

Digital Subscription

Original price was: $17.00.$15.00Current price is: $15.00. -

Single Digital Issue

$5.00 -

Single Issue

Original price was: $10.95.$9.95Current price is: $9.95. -

Subscription

Original price was: $32.00.$25.00Current price is: $25.00.